MONROE COUNTY - According to Dr. Dan Vimont of the Director of the UW-Madison Center for Climatic Research, we are “never going back to the climate we had in the 20thcentury.” Vimont spoke to members of the Monroe County Climate Change Task Force at their January meeting.

The planet crossed the 400 parts-per-million (ppm) threshold for levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere in November of 2015. Since then, levels have continued to rise precipitously, measured at 415 ppm in 2020.

When asked about the much-discussed impacts of reduced emissions during the global COVID-19 pandemic, Vimont said that the effects were really “just a minor blip.” He said that the carbon emissions in 2020 were only about 10 percent less than the amount of emissions that would otherwise have been expected.

“We don’t need to tear down the economy to reduce carbon emissions,” Vimont explained. “Climate Change mitigation is actually an economic opportunity, with many markets such as alternative energy, carbon farming, and more having been neglected.”

Vimont explained that every dollar our state spends on fossil fuels is money that is sent out of our state. He said that the business community has already moved on, and that is because investing in climate change mitigation makes good business sense. He said that it will give businesses greater control over their costs.

“The goal has to be net zero carbon emissions,” Vimont said. “And there is no future for the planet that will not involve geoengineering. Removing carbon from the atmosphere will stimulate a tremendous market.”

Historic changes

As Vimont explained, global temperature has already warmed by about one degree Celsius (C) from 1880-2019. Responding to what was a recognition of a historically unprecedented rate of change, and hitting the 400 ppm rate of CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere for the first time in April 2014, countries came together to sign the Paris Climate Agreement. One of the key goals of that agreement was to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below two degrees C above pre-industrial levels.

“CO2 and other greenhouse gases are increasing due to human emissions,” Vimont said. “In Wisconsin, we are two-to-three degrees Farenheit (F) warmer than we were in 1950, and will warm another two-to eight degrees F by 2050.”

Vimont, a Professor of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at UW-Madison, is one of four scientists who lead the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI).

“What we do now to reduce emissions won’t have that much of an impact on the conditions that we experience in 2050,” Vimont explained. “But it will have an enormous impact on the conditions that we see in 2100.”

Vimont said that citizens of the planet and the state can expect to deal with the impacts of climate change for the next generation or two, even if strong steps are taken to reduce emissions and mitigate and adapt to changing conditions now.

“All we can do at this point is to reduce the rate and amount of emissions, and plan for the inevitable,” Vimont said. “That inevitable will come in the form of a warmer and wetter climate.”

Seasonal variance

Vimont explained that in Wisconsin, warming is not uniform during the seasons. What is happening is that the winter and nighttime temperatures are warming more than temperatures in the other three seasons or during the day. In addition, most of the increased precipitation is seen in the winter, spring and fall.

“The impacts of warming in winter can be seen in agriculture, in the hydrology of our lakes, in tourism, and even in logging,” Vimont said. “We can also expect to see a continuation of the trend for more extreme weather events – both rainfall, as well as drought.”

Vimont referenced how planners at Fort McCoy, for instance, are already taking expected warming into account in planning training operations. Days of extreme heat are expected to double by 2050. The Wisconsin Department of Health is also concerned about the increased need for cooling centers to help citizens survive extreme heat events, and the need to put in place social networks to check on vulnerable citizens.

“The Driftless Region is more fortunate than other areas of the state in terms of the impacts of warming on trout streams and fishing tourism,” Vimont said. “This, he explained, is due to the fact that streams in the area are significantly fed by groundwater and springs, which tend to be colder.”

Other areas not so fortunate can expect more severe impacts on fish populations. He said that warmer streams tend to reduce native brook trout habitat and increase brown trout habitat.

“Wisconsin can expect to see less warming during summer days,” Vimont explained. “But even so, our summers will warm by one to seven degrees F by 2050. Global temperatures will warm by about three degrees F (1.5 C) by 2050, and by two-to-four degrees C (3.5-7.5 degrees F) by 2100 at the current rate.”

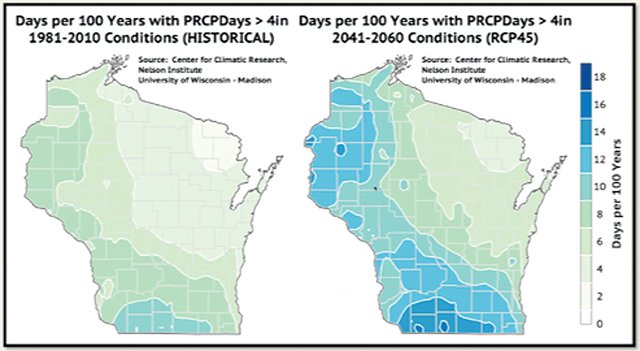

As far as increasing precipitation trends, Vimont confirmed that Wisconsin has just lived through the wettest decade on record. He explained that there are regional differences in the increase, and that Southwest Wisconsin has been hit particularly hard, with precipitation levels up by 20 percent.

“Of course, it needs to be said that increased runoff and flooding is not only due to climate change,” Vimont said. “It is also due to upstream changes in land use that decrease the amount of water the landscape can infiltrate, as well as to some natural variability.”

Mitigate and adapt

Vimont finished by explaining that the two major options available to deal with the impacts of climate change are mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation is a way to slow and reduce dangerous amounts of climate change. Adaptation is the way to reduce the impacts of changes that have already happened or that will happen in the future.

Monroe County Highway Commissioner Dave Ohnstead is grappling with the impacts of climate change first hand. He pointed out that even if infrastructure such as bridges were to be modified to adapt to increasing precipitation, it would also require changes in the roadbeds that lead up to the bridges.

“In our county, in many locations, if we were to make the bridges larger, we would have to make changes to roadways, which would have impacts on wetlands,” Ohnstad said. “When we start to have impacts to wetlands, what impact will that in turn have on mitigating effects of climate change such as runoff and flooding?”

Another participant asked Vimont what the impacts would be for major commodity agricultural crops such as corn and beans.

“There will be competing effects for crops,” Vimont said. “An up side may be a longer growing season, but the down side is increased precipitation in the spring which can delay planting. Also, more warm and humid conditions in the growing season have potential to reduce yields and increase pests.”

Vimont said that agriculture has been adapting to climate change “on the fly” for the last 30 years. He said that some of the best options for climate change mitigation exist within agriculture, and that this is also a tremendous economic opportunity that so far has been largely neglected.

Tim Hundt from Congressman Ron Kind’s office asked if ‘regenerative’ agricultural practices, which can both increase carbon sequestration in the soil, as well as water infiltration, might be a big part of the solution.

Monroe County Conservationist Bob Micheel responded that carbon farm planning has gained increasing traction at the state level. He said that the advantage of promoting agricultural production methods that increase carbon sequestration is that those production methods also help to reduce runoff and flooding, and protect groundwater.