DRIFTLESS - Last week, two meetings apiece were held in the West Fork Kickapoo and Coon Creek watersheds for the purpose of obtaining public input about ‘factors to consider’ when engaging in planning for what to do about flood control dams that breached in August of 2018. Over 100 citizens and agency professionals participated in the meetings. Both of these watersheds contain flood control dams that failed in the catastrophic rain event of August 27-28, 2018.

“The focus of these meetings is to obtain citizen feedback about social, environmental and economic factors that could influence the planning process for these watersheds,” Robb Lutz of EA Engineering told meeting participants. “We have access to all kinds of information from the counties and other agencies, but we know that citizens who live in the affected areas know things that we won’t be able to get from those other sources.”

At the first meeting in Cashton, USDA-NRCS Assistant State Conservation Engineer Scott Mueller clarified what the purpose of the planning process is:

“The primary purpose for planning is flood prevention or flood damage reduction in the Coon Creek and West Fork Kickapoo valleys,” Mueller said. “The need for planning arises from the failure of five flood control dams during a flood in August 2018.”

As presented by the team, made up of USDA-NRCS staff, and contracted engineering and economic analysis professionals, the total watershed planning process will involve a total of seven steps. The meetings last week were the first of seven steps, called ‘IDENTIFY problems and opportunities.’ This will be followed by:

INVENTORY and forecast resource conditions

FORMULATE alternative plans

EVALUATE alternative plans

COMPARE alternative plans

SELECT the locally preferred alternative

SUBMIT request for funding and design

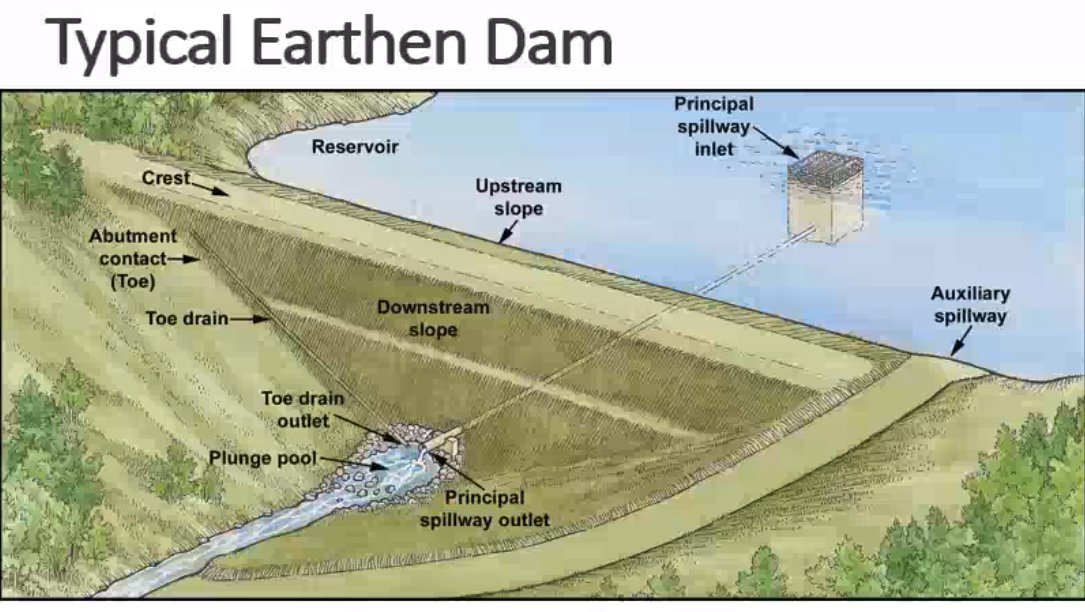

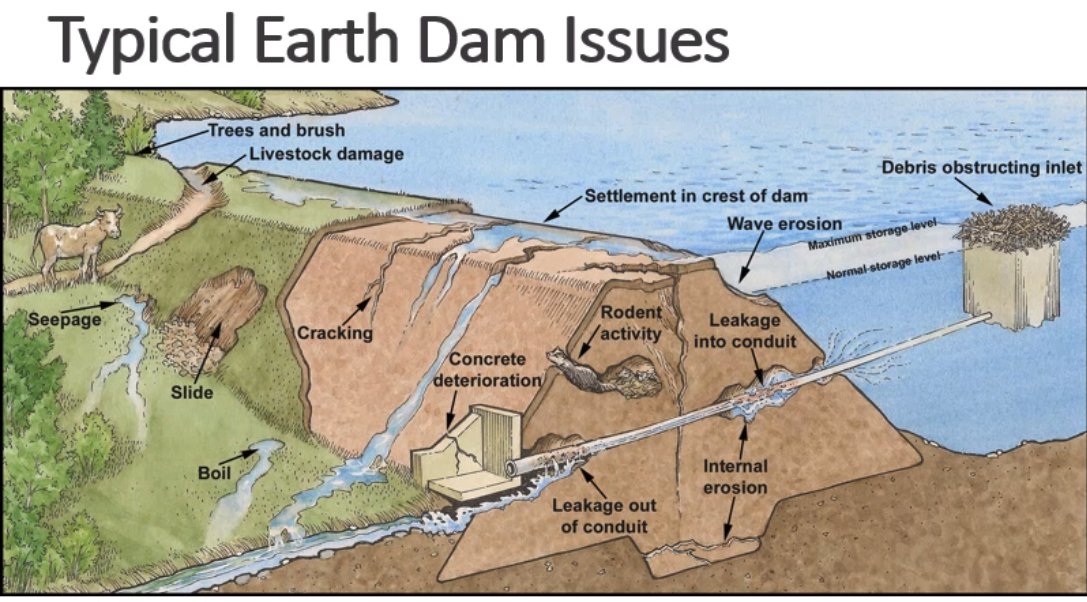

Engineer Robb Lutz gave participants an overview of terminology used in describing the different components of earthen flood control dams, and also an overview of the kinds of problems that can develop with them. Those include deterioration of concrete and metal components used in construction; cracking in the earthen structure of the dam; development of internal voids in the dam; erosion of areas of the dam; internal erosion, and more.

Lutz told meeting participants that generally the options being considered to address the breached dams are repair where they currently are; replace where they currently are; relocate; and remove.

“Given the extent of damage, and the fact that the breaches are eroded down to bedrock, we don’t really see repairing the structures where they’re currently located as a viable option,” Lutz said. “Given the damage to the bedrock hillsides in the current locations, even replacing them in the same location will probably not be a viable option. So the two most likely scenarios will be relocation or removal.”

Lutz explained that if the decision made by the local sponsors (LaCrosse, Monroe and Vernon counties) is to remove the dams, then NRCS would do what was necessary to return the stream corridor to a stable condition through grade stabilization and restoration of the area.

“If the decision is to remove the dams, then we would be looking at other ways to provide flood control,” Lutz said. “All of the work that we are doing is to help the dam owners – the counties – make the decision about what to do with the breached structures.”

Vernon County Supervisor and Town of Webster board member Ole Yttri asked what the primary factor was that led to the dam failures.

“Was it just the rainfall volume that was the biggest problem?” Yttri asked.

“The dam failure analysis that was completed in June of 2019 indicates that the cause of failure was a combination of the volume of rainfall and the structural weaknesses of the underlying geology,” Lutz responded.

Monroe County Board Supervisor Jen Schmitz asked if the failures would have resulted if the ground had been dry versus saturated.

“Our team is currently conducting a Hydrology and Hydraulics (H&H) Analysis that will get at answering that question,” Lutz responded.

Wisconsin State Assembly Representative Loren Oldenburg asked if the planning process would look at the changes in land use today versus in the 1960s to determine what difference that made in the dam failures.

“We will be modeling different land use treatments in our cost-benefit analysis to determine what changes could be made that would move the dial,” Lutz said.

LaCrosse County Town of Washington board chairman Dan Korn seemed happy to hear about the engineers’ early assessments of what solutions would be most likely.

Lyndon Luckasson, whose family’s lands the breached Luckasson Dam is on, pointed out that there have been many infrastructure and streambank improvements to the Coon Creek watershed since the 1960s. He asked whether the floods would have happened if there were no dam in place.

“This is one of the types of question we will try to answer with our H&H analysis,” Lutz said. “We will create a flood inundation map both with, and without the dams in place, and a corresponding economic analysis.”

Factors and services

Participants at the meetings were led through consideration of a list of ‘factors to consider in planning,’ and also ‘ecosystem services that could be impacted by selection of a flood control alternative.’

It was clarified in this process that these factors and services are typically considered at such time as one or several possible alternatives have been selected.

“What we’re asking you to do here today is a little cart-before-the-horse, because we have such an aggressive timeline for this project,” Sundance’s Keri Hill said. “So what you need to do is imagine possible impacts from the four big buckets of possible alternatives – repair, replace, relocate or remove.”

Factors included were: Cultural and Historical Resources; Ecologically Critical Areas; Scientific Resources; Endangered and Threatened Species; Fish and Wildlife; Essential Fish Habitat; Migratory Birds; Invasive Species; Riparian Areas; Wetlands; Land Use; Forest Resources; Soil Resources; Prime and Unique Farmland; Farmland of Statewide Significance; Floodplain Management; Regional Water Resource Plans; Water Resources; Sole Source Aquifers; Waters of the United States; Special Aquatic Sites; Wild and Scenic Rivers; Air Quality; Public Health and Safety; Social Issues; Environmental Justice; Civil Rights; and Coral Reefs.

Ecosystem Services considered were:

Provisioning: food, fiber, water, timber, and biomass

Regulating: air, climate, disease, erosion, natural hazards and pests, pollination, and water purification

Supporting: nutrient cycling, soil formation, and primary production

Cultural: aesthetic (viewsheds), recreation, ecotourism, and spiritual/religious

For those who did not provide input on these topics at the meetings, comments will be accepted through October 16. Options to submit input include:

Website: there is a comment form available on the project website at www.wfkandccwatersheds.com

E-mail: Keri Hill at khill@Sundance-inc.net

Call: Keri Hill at 208-274-9004

U.S. Mail: 305 N. 3rdAvenue, Ste. B, Pocatello, Idaho, 83201

Land use big topic

Each of the flood control dams that failed is designed to control water from a specific drainage basin. In the original watershed plans, it was a combination of conservation land use practices such as contour strip cropping, diversions, terraces, pasture renovation, and streambank protection, along with the flood control dams that were meant to work together to control flooding.

In the original watershed plans for the two watersheds, land use treatments were expected to contribute to flood reduction. The local soil conservation district was required to obtain conservation agreements to carry out conservation farm plans for at least 50 percent of the land above each structure as a condition of being able to obtain the financing for construction of the dams.

The plan read, “The land treatment practices… will reduce runoff and erosion, increase infiltration rates and water-holding capacities, and improve the hydrologic conditions of the watershed.”

The Coon Creek Watershed Work Plan was the first of its kind to be developed by the NRCS (formerly Soil Conservation Service). The major problems in the Coon Creek watershed in 1958 were floodwater damages to crops and pasture, fences, farmsteads, machinery, buildings, livestock, county and township roads and bridges, and urban areas of Coon Valley and Chaseburg. Project measures implemented under the Watershed Work Plan included a multitude of land treatment practices to reduce erosion and improve the hydrologic condition of watershed; and 14 flood control dams with a total capacity of 1,160 acre-feet to regulate flood flows from 20.75 square miles, or 27 percent of the watershed above the village of Coon Valley. The benefit-cost ratio for the project was about 1.2:1.

Project measures implemented under the 1961 West Fork Kickapoo Watershed Work Plan include a multitude of land treatment practices to reduce erosion and improve the hydrologic condition of watershed; and seven flood control dams with a total capacity of 3,652 acre-feet to regulate flood flows from 30.73 square miles, or 31 percent of the watershed above the village of Liberty. The benefit-cost ratio for the project was about 1.2:1. With the two dams built under the Pilot Watershed Program, the runoff from 34.6 square miles or 35 percent of the watershed above the village of Liberty is controlled.

“There was a history in these watersheds of big cooperation, and big land use changes – a general shift in the land use mindset,” Lutz said. “However, it is out of the scope of our planning process to formulate additional land use regulations.”

Lutz said that one of the things that has surprised him the most in the four meetings was that farmers were telling him that they wanted to see incentivization of conservation land use treatments.

When asked who had historically made the decision to require that 50 percent of landowners in the watersheds be cooperators with the Soil Conservation District – SCS, the counties, or both – Lutz said that he was not sure about that.

“We can’t withhold the flood control benefit if landowners won’t make changes,” Lutz said. “But I think we’re on to something with the idea of incentives.”

He was then asked if his team could “design its way out of the runoff and flooding situation without taking land use into account.”

Keri Hill responded, “No, we can’t over design bigger and bigger structures to account for poor land use decisions. NRCS has minimum standards for the land use in a drainage basin controlled by a flood control structure.”